This is a guest post by Learning Service follower Elizabeth Bezark.

Part I

Thank You for Staring: A Day in the Life of an Unengaged Volunteer

During my first international community engagement experience, my group and I took a daylong break from learning how to build fuel-efficient cookstoves in Antigua, Guatemala to visit a local school down the road from the stove factory. An image from that school visit remains clear in my mind after four years: A group of twenty elementary school students sat in desks with their hands politely folded in front of them. Their dark-blue uniforms contrasted with the pink, green, and blue pastel wall behind them. My group of ten mostly white university student volunteers, dressed modestly but more casually than the children, sat in rows of desks on the other side of the classroom, too far away to interact with or hear each other. We listened to a few songs in Spanish and a few songs in English and otherwise continued to sit separately at a distance. For hours.

Schools in rural communities are not zoos.

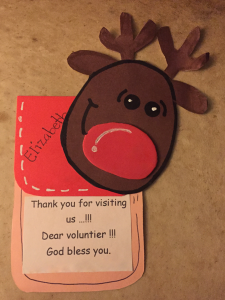

THE CARD THE CHILDREN MADE FOR THE VISITING VOLUNTEERS

Later that day, the students called our names to give us thank you cards that they made prior to our visit. I could tell their class had spent hours on this craft project. Before passing out the cards, the students performed a talent show for my group, including a few common Guatemalan songs and dances. While I appreciated the kindness in their gesture, it felt emphatic and misplaced in context. I kept asking myself: Why are we here? What exactly are the students thanking us for?

After asking my program coordinator those very questions, I learned that that day was a holiday for the students during which no instruction was planned, so our presence did not take away from their learning time. However, I walked away from the experience feeling that their display of gratitude didn’t match my group’s level of engagement. The focus of the program I had traveled with was experiential education, which for those who don’t know means education through having an experience, reflecting on it, learning from the reflection, and then using that learning and reflection to plan for the next similar experience. My program leaders weren’t aware that there were no activities planned for that specific day, and neither they nor the program coordinators, nor the school’s teachers used any backup activities from their experiential toolkits. The students essentially thanked us for staring at them. Had we understood that the school had no need for volunteer support that day, and that the school hadn’t planned activities, most likely because they expected us to come up with some, we should have reconsidered visiting at all. Schools in rural communities are not zoos.

In hindsight, activities such as us performing an impromptu talent show for or with them or bilingual language exchange activities would have created monumentally more meaningful interactions. The students could have taught us a few words in Kaqchikel or Spanish, and we could have taught them some words in English. The program coordinators could have brought some bilingual storybooks along. The language barrier could have inspired mutual learning. Why didn’t the people preparing the structure of the program plan for meaningful, interactive activities as backup for these situations? Why didn’t we make thank you cards to show appreciation for our time with them as well? Instead of spending hours staring at each other and breaking the silence only with a few songs, someone could have taken initiative to make that day more engaging. This could have been me, and I take accountability for my part in the lack of initiative to foster meaningful engagement.

If more groups showed up periodically, I would likely have begun to really question their presence.

After I returned to the States, I learned that the school’s partner organization, with which my alma mater contracted for this program, visits the same school during multiple programs each year. While I don’t have information on the other groups’ activities and the school owners’ perspective on any of those groups, I still wonder about the impact of multiple groups passing through every year. Did my group’s one session with the school create an ideologically problematic situation on its own? Not necessarily. However, considering that my group was one of many that the students had encountered, I wonder: Do they ever grow tired of calling names of volunteers they’ve never met before and will likely never see again? Is singing and dancing for strangers a norm for them?

If I were nine years old and one group of college students from Guatemala came to my school for a similarly-arranged day, I probably would have thought that that time together was fun. I would have enjoyed seeing people from a different culture. If the college students sat across the room from my class for a few hours and if we didn’t interact, then I would likely have felt slightly confused. If more groups showed up periodically, I would likely have begun to really question their presence. I wonder if and when the students at that school in Antigua began to question the presence of groups of volunteers passing through their classroom on a regular basis.

To be fair, my group did interact with the students during the last half-hour of our day there. We played jump rope and picked flowers together with the students. My friend and I made daisy chains with one of the students who told us that she enjoys math. I told her that my favorite subject was math when I was her age too. If only it hadn’t taken hours to realize that staring at each other was not interactive. The end of the day went better than it began, and I only wish that the majority of the day had been worth their gratitude.

Do schools in the States normalize visits from groups of college students from other countries on a regular basis?

Additionally, analyzing this situation over the years has illustrated for me that ideas such as community engagement and the impact of volunteer groups don’t always land on a positive-negative binary. While most of the day’s inactivity in no way warranted their emphatic display of gratitude, we did eventually interact with the kids, which was fun for all involved. Our day had a rocky start and a more positive end. My program included a pre-departure orientation on the potentially negative impacts of voluntourism, emphasizing the need to continuously reflect on our intentions and impacts. Thus, none of us walked away thinking we had saved the world or that we were the students’ only source of joy for the rest of that year. This pedagogy is to that program’s credit. However, as far as I know I was the only student who questioned our presence during the school visit portion of our program. This situation taught me to think critically about community engagement. Sitting in desks and staring at a group of children constitutes neither learning nor serving. Such a situation perpetuates school visits in rural communities as a norm in voluntourism programs. To repeat my sentiment from earlier, this practice treats schools in rural communities essentially as zoos. Do schools in the States normalize visits from groups of college students from other countries on a regular basis, legitimatizing their presence with the title of ‘volunteer’? You know the answer to that.

This problematic school visit guided me to seek more engaging learning service opportunities. It taught me that program marketing and excellent orientations do not always translate to meaningful engagement on the ground, especially when program delivery results from multiple partner organizations with different priorities.

Part II

Short, Sweet, and Simple: Community Engagement Through Learning Service

A CREEK ON THE SCHOOL GROUNDS IN THAILAND

A few years after my time in Guatemala, I journeyed to Thailand with an international experiential education provider that emphasized ethical learning service and meaningful travel. I didn’t expect this provider to deliver an engaging program perfectly, however, I thought they would have done so better than a small student organization nestled deep within a university structure. During my program in Thailand, my group spent a week with a permaculture education center and organic farm in Nan.

While there, I learned about organic farming, and I learned how to cut bamboo strands to weave into baskets. As needed, we followed the direction of the farm’s owners in digging rain trenches and planting bulbs. When we participated in these activities, we understood that our short-term contribution was part of the long-term sustainability of the farm, which existed before we arrived and which continued after we left. On days when the owners didn’t require volunteer support, we followed the sabai sabai (which roughly translates to ‘laid back’ or ‘relaxed’ if I remember correctly) culture of Thailand and spent time just being. We learned how to cook green curry from ingredients grown right there on the farm. We wove baskets from bamboo that we cut down in the forest and sliced into strands.

We understood that our short-term contribution was part of the long-term sustainability of the farm.

During our time at the farm, we did spend time at a school. However, this time, we had a plan. One of the owners of the permaculture education center teaches English, and she planned this visit as an opportunity for her students to interact with native English speakers. We spent a few hours with the students, during which time we sat in a circle small enough so that we could all hear each other. We introduced ourselves and then talked about our favorite subjects in school. We learned a few Thai words as we taught them a few English words, and then we had lunch and left. It was a simple interaction that did not involve any elaborate thanking rituals. There were a few silences, maybe even awkward silences, but those did not last hours. The primary teacher of that class planned the short activity with our group, we followed her plan, and then we left to explore Nan while the teacher continued with her day teaching the students.

THE SCHOOL IN THAILAND

The example of more meaningful service was an example of a simpler activity. In the voluntourism industry, there seems to be an expectation for community engagement to have extreme impact and a very hands-on approach. However, this doesn’t always make sense. My program in Antigua used hours of time unproductively and involved the students’ elaborate thanks. My program in Nan involved a short and sweet, structured activity and a simple exit. Sitting around and staring at students in a school in Antigua does not warrant a talent show and thank you cards from elementary school students. Sitting in a circle and exchanging a few words with students at school in Nan and parting on simple terms also does not, but it illustrates a healthier example of engagement. One might still question whether or not multiple groups visit that school in Nan during a given year, and one might reflect on the impact of this, even though this second story illustrates learning service done better. Active learning took place. Active reflection is still necessary.

There seems to be an expectation for community engagement to have extreme impact and a very hands-on approach.

I don’t claim to have a definitive solution to learning service fails, nor a definitive formula for learning service wins. However, I conclude with some questions for reflection while choosing a learning service program to participate in or to lead.

- What constitutes meaningful community engagement?

- What activities will participants engage in? Who will select these activities?

- What aspects of the voluntourism industry breed elaborate gratitude rituals that don’t necessarily depend on a group’s in-practice activities?

- When is it appropriate for one group to spend time at a school? What about multiple groups throughout a year?

- Are a provider organization’s partnerships within host communities (with local non-governmental organizations, with local schools, with homestay communities etc) healthy? From whose perspective?

- What does a healthy learning service experience look like in practice?

I invite readers of this post to use these questions to reflect as I do the same on my learning service journeys.

Elizabeth Bezark is a University of Oregon graduate with a BS in International Studies (Honors with an emphasis in sustainable development). She has strong passions for meaningful travel, ethical community engagement, and intercultural education. She sees these practices as valuable ways to foster global citizenship in herself and others. She is a current student of the Omprakash EdGE (Education through Global Engagement) program, and she’s currently studying Spanish to prepare for extended time in Perú next year. The main image shows the elementary school in Guatemala that Elizabeth visited.

Interesting thoughts. I think even the best trained foreign workers struggle with what real impact they’ve been able to accomplish. Many Peace Corps Volunteers would agree with you and me. I think probably a program of a year or more is better, but sometimes the philosophies of other countries are just to different.

I agree with you that a year or more is best in order to create mutually-beneficial engagement. The programs I’ve participated on have varied in length in terms of the whole program, but have always been short term per host community (four days at the most in a given location). The more I reflect, the more I think that these short-term engagements benefit primarily the volunteers and might even distract host NGOs from their work in certain cases. Also the more I reflect the more I see school visits as strange, unless someone teaches English or another foreign-to-the-students language for a year. I opted out of one of two school visits during my program in Thailand and the next time I have an opportunity to visit a school while I’m in a new community, I’ll mostly likely opt out unless I get to know a family well.

The Peace Corps is interesting because volunteers stay with the same community for two to three years. They’re not moving from place to place on a gap year or international experiential education program. I also like about PC that, nowadays, host communities have to request a PC volunteer. Service isn’t imposed by people of privilege who think that their way of life is superior to that of their host community in the context of PC like it seems to have been in the 1960s and 1970s. I might not have all of the facts on this, so please correct me if I’m wrong on PC. It does seem like these days, PC is much more holistically-minded and culturally respectful.